M-001: Autopsy of a Pine-Needle Mystery

Documenting my attempt to isolate and grow wild mycelium from pine needles—a short experiment in field mycology, contamination, and knowing when to let go.

Listen to this post

In early winter I went hunting for a stranger living under the loblolly pine in my front yard.

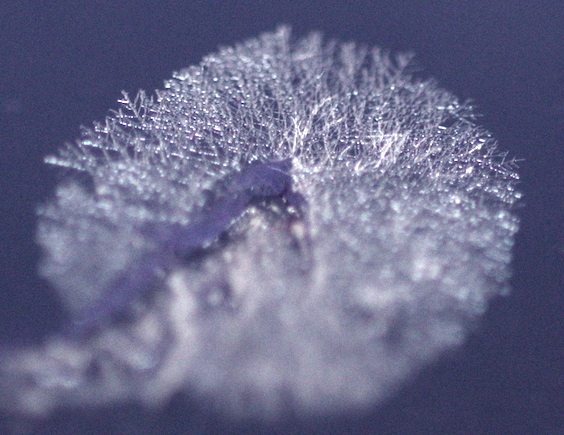

If you peel back the mat of needles and leaf litter there, you find it: a white, fibrous web threading through everything. In the field it just looks like “forest fuzz,” but under a macro lens it turns into a landscape—little bridges, fans, and sheets stretching between pine needles and bark. That’s what I decided to bring inside.

I didn’t know what species it was. I just knew there was a lot of it, it was doing fine in terrible soil, and I wanted to see if I could isolate it and grow it on my terms.

I called it M-001.

Collecting the sample

Two days before my first notebook entry, around 1600, I scooped a handful of that pine-needle mycelium into a container and brought it into the house. It came in attached to its whole neighborhood: needles, bark flakes, dirt crumbs, and whatever microscopic roommates it had picked up outside.

I worked inside a still-air box—something I’ve used before, just not yet for this particular mystery guest. The plan:

- Split the sample across four petri dishes

- Pour one extra plate as a control and never inoculate it

- Watch what happens

On November 30, 2025, I wrote:

“Two days ago at ~1600 I collected a sample of mycelium living in the pine needles under loblolly in front of the house. I split the sample between 4 petri dishes with one control… I’m calling this sample M-001.”

The first observations were surprisingly encouraging:

- Control – clear

- PD-1 – rapid rhizomorphic growth from 5 points, largest about 0.5”

- PD-2 – rapid rhizomorphic growth from 8 points, largest about 0.125”

- PD-3 – rapid rhizomorphic growth from 3 points, largest about 0.25”

- PD-4 – rapid rhizomorphic growth from 2 intersecting points, largest about 0.625”, second about 0.5”

In other words: everything I actually touched with forest material was exploding with white, rhizomorphic growth. The control, which never left the SAB during pouring, was spotless.

I ended that first entry with the obvious caveat:

“No contamination noticed, but these were collected outside and contain competition seen with a macro lens, so it’s just a matter of time.”

I knew I hadn’t brought in “a single fungus.” I’d brought in a tiny ecosystem and was betting I could outrun everything except the thing I wanted.

Macro close-ups of the pine-needle sample on the teal background, showing the white strands wrapping needles and bark.

Macro close-ups of the pine-needle sample on the teal background, showing the white strands wrapping needles and bark.

Contamination arrives (right on schedule)

The next morning, December 1, that bet started to look shaky.

By 0700, the plates still looked clean enough that I didn’t log anything dramatic. By ~1400, everything had changed:

“All samples show contamination, but control is still clear, so the contam is natural. I suspect I’ll have to transfer the best looking ones tonight. This morning I observed no contamination at 0700, but now we’re almost too late.”

The forest had followed M-001 indoors.

The control plate staying clear strongly suggested the worst of the contamination came in with the original outdoor material, not from the agar or the SAB itself. That said, I was collapsing and re-setting the SAB between work sessions, so I can’t pretend technique was completely out of the picture either.

Still, if I wanted an isolate, I needed to move fast.

I started prepping WBS spawn so that, if I managed to grab a clean slice, I’d be ready to run with it. That afternoon I picked the best candidate:

“Transfer completed. 4 sections were taken from sample 3. Sample 3 had no mold sporulation, the others did.”

Sample 3 became the donor for a new set of plates, labeled A–D.

Second chances: plates A–D

On December 2, the notes read (under “from first set”):

“Control is still clear with positive growth in B, C, D… A contains no growth, I think I failed to transfer anything. B – steady growth from center ~0.5 in C – 2 sectors each growing out from a focal point, ~0.25 in growth for both. D – 3 sectors, possible contam – fuzzy, maybe tomentose growth.”

So at that point, the situation looked something like this:

- The same original control plate was still perfectly clean.

- B and C were coming along nicely.

- D was suspiciously fuzzy.

- A looked like a dud transfer.

Not ideal, but not hopeless. If even one of those sectors stayed clean, M-001 could survive its first encounter with the indoors.

Then December 3 gave me a small plot twist:

“Good news. A is inoculated and looks the cleanest so far. B or A are the most aggressive. I don’t think, after another day, that any are contaminated (showing signs of). C & D are showing signs of tomentose growth.”

Somewhere in the smear of Sample 3 that I tried to move to plate A, a tiny bit of mycelium had in fact made it over. It just took its time declaring itself. When it finally did, it looked like the best candidate of the bunch.

For about 24 hours, it genuinely seemed like I’d salvaged the project.

The little island of feathery mycelium fanning out on dark agar.

The little island of feathery mycelium fanning out on dark agar.

The black-spore surprise

The end came fast.

On December 4, I woke up optimistic:

“Morning: A is looking gorgeous! D might be contaminated, if I only had a magnifying glass, I would know for sure. Lots of healthy growth in all of them. Control from the first batch is still clear.”

Three hours later:

“11:45am – all are contaminated… black little spores present in all… completely undetected 3 hours ago.”

Whatever mold had been biding its time finally decided to sporulate, and when it did, it dusted every single plate—including the ones that had looked clean just a few hours earlier. The clean, lonely control plate sat off to the side, still pristine, watching the carnage.

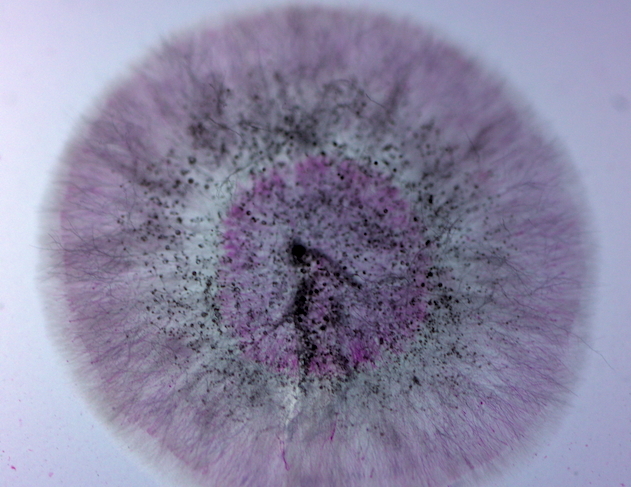

The contaminant that killed the M-001 plates: a dense, pink-lavender mold colony with a halo of fine hairs and scattered black spore heads across the center.

The contaminant that killed the M-001 plates: a dense, pink-lavender mold colony with a halo of fine hairs and scattered black spore heads across the center.

By that afternoon, the practical situation was:

- All M-001 plates: compromised

- My stack of dishes: basically empty

- Four new commercial strains arriving this week, all of which actually deserved clean agar and attention

So I made the call: retire M-001. No more heroic transfers, no more time poured into an ecosystem that had clearly voted for mold.

What I learned from losing M-001

Even for a short, failed project, M-001 taught me quite a bit:

Controls are worth the plate. That one control—same plate throughout—stayed crystal clear the whole time. It gave me a baseline and a reality check. Whatever chaos I saw everywhere else, I knew what “clean” looked like in this setup.

Field mycelium is a package deal. You don’t just grab “a mushroom” from the woods; you grab its entire social circle: molds, bacteria, yeasts, and whatever else has been competing with it in the mulch.

Contam doesn’t always announce itself early. For several days, the “good” plates looked fine to the naked eye. The black spores only became obvious right at the end. A magnifying glass or microscope would have shown me the warning signs earlier.

The SAB is a tool, not a force field. Working inside a still-air box helps a lot, but collapsing and resetting it between sessions—and working with dirty outdoor material—means I can’t blame or credit technique alone. It’s part of the story, not the whole story.

Documentation turns failure into data. Having dated notes—“no contam at 0700,” “almost too late by 1400,” “black spores everywhere at 11:45”—means I can reconstruct what happened instead of just remembering a vague sense of “it all went bad.”

Resources matter. Hobby mycology is always resource triage: dishes, agar, time, and brainspace. With four new strains on the way, keeping a doomed wild isolate on life support didn’t make sense.

What’s next

M-001 as a lab project is over, but the organism itself is still out there, quietly running decomposer operations under that same loblolly pine. If I come back to it later, I’ll do it with more plates, better magnification, and maybe some selective media to give it a fighting chance.

For now, M-001 gets to stay what it originally was: a mysterious white web in the pine needles, starring in a set of macro photos and a few pages of my notebook.

Honestly, that’s not a bad first chapter for a wild strain that never asked to be domesticated.